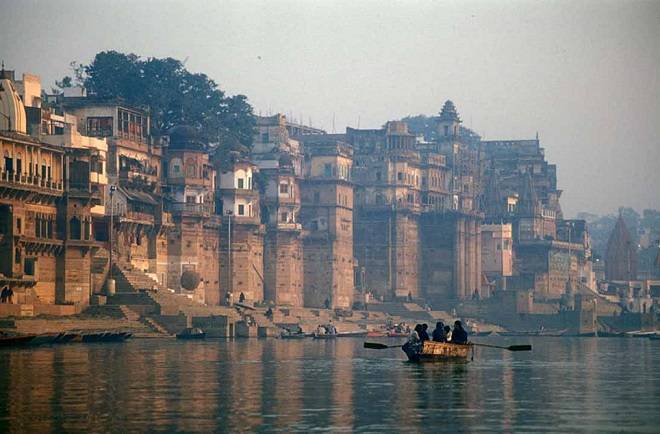

Calendar art depicts Ganga Maiya as a beautiful full bodied lady venerated by millions, yet her devotees violate her guiltlessly. Electoral promises to clean up the Ganga wins votes but nothing then prevents the same voters from misappropriating funds allocated for the job. In this environment of grotesque irony, what are we to make of the Uttarakhand High Court’s judgment declaring the Ganga and Yamuna as living beings? Coming as it does at the crest of a saffron political wave, are we to understand that India is capable of cleaning up its rivers only by reaching back to a 5000 year old concept of riverine goddesses? Does modernism mean retro chic Hinduism? Do we need to call our aerospace initiative the UdanKhatolaProgram? Are our solar energy farms an aspect of Surya Pooja? Is Hindutva the framework within which Indian business will now seek to achieve its commercial ambitions?

To make sense of this unusual judgment [Mohd. Salim v/s State of Uttarakhand, W.P. 126 of 2014 Decided 20.03.2017], we need to examine what it means in law for a ‘thing’ to become a ‘real’ legal person. Consider a Hindu temple. People routinely offer money to the deity within. The money accumulates. Priests then create trusts, open bank accounts, invest the money and so forth. Sometimes, they also open schools, colleges, charities and hospitals. Who owns all these things? Clearly, it’s not the priests. In YogendraNathNaskar v. Commission of Income-Tax, Calcutta [1969 (1) SCC 555], the Supreme Court reiterated yet again that a Hindu idol is a juristic entity capable of holding property and of being taxed through its managers who are entrusted with such duties.

So far so good, but we now face a fundamental difficulty: how do we take a 2500 km long river and make a ‘person’ out of it? The Supreme Court has given us the necessary ideological construct to justify this piece of legal jugglery. In Ram Jankijee Deities & others v. State of Bihar [1999 (5) SCC 50], the Supreme Court more or less endorsed the hardcore Hindu mind set: “Images according to Hindu authorities, are of two kinds: the first is known as Sayambhu or self-existent or self-revealed, while the other is Pratisthita or established. A Sayambhu or self-revealed image is a product of nature and is … without any beginning and the worshippers simply discover its existence”.

In effect, this means that a river for instance is holy before the beginning of time and humans have merely stumbled on something self-evident. In this view of the matter, the Uttarakhand High Court didn’t give us anything, it merely stated the obvious.

At one level, river or idol, all artificial persons are made equal because they are after all only ideological constructs. Indeed, the idea of a ‘real person’ is itself an ideological construct. In history, we have had legal systems where real ‘touch and feel’ human beings were not legal persons. For example, in Roman and French colonial law, a slave was never a person. This was also true in America till slavery was abolished. Conversely, even societies that pay little if any heed to religion have recognized a multitude of imaginary secular ‘things’ as real persons. What is a company but words on paper that exists an entry in a register in some government office somewhere? What is a Hindu joint family but an emotional construct in the minds of blood relatives? What are charitable trusts but the benevolent fantasies of the dead? Yet all these are legally real entities even though they are not real people. This brings us to the heart of the real issue. If you stop to think about it, human beings are all committed irrevocably to ‘imagined realities’. The Gods, Hindu Karma, Chrisitian Charity, Original sin, Bhakti,Nirvana … you name it. If the Indian Evidence Act is the standard of proof required to make something real, none of these ideas can be proved to a standard that a court could accept. Indeed, if the Indian Evidence Act is the standard of proof, the concept of human rights, justice and fairplay are all imagined realities. Yet, from this reality comes the judicial system, however, imperfectly it administers its own mandate. That being the state of the art, there is no special reason why a river should be less a pretty lady and more a bulk of water seeking the lowest point in the landscape to flow through.

This brings us back to the judgement of the High Court. The saga began when some persons encroached along the right bank of the Shakti canal in the Kulhal District of Dehradoon and started raising a building. Neighbours complained. The administration acted but it was unclear if this land fell within Uttarakhand or was a part of Uttar Pradesh. The dispute ultimately negotiated the labyrinth of India’s judicial system and came to rest in the High Court. The court took the view that Indians have deep veneration for the Ganga and the Yamuna, which rivers have provided both physical and spiritual sustenance to all of us from time immemorial. For this reason, they must be recognized as living persons, especially in view of Articles 48A and 51A(g) of our constitution. In conclusion, the court declared the Director NAMAMI Gange, the Chief Secretary of the State of Uttarakhand and the Advocate General of the State of Uttarakhand as persons in loco parentis (meaning “in place of the parents”) as the human face to protect, conserve and preserve Rivers Ganga and Yamuna and their tributaries.

The real question though is the impact of this judgment. What happens if an imagined reality becomes a real person? For a start, it invokes the power of the state to intervene against an abusive or negligent parent, legal guardian or informal caretaker, and to act as the parent of any child or individual who is in need of protection.Thus, the court has now obliged the state to protect the rivers. Does this advance the cause of environmental protection in India?

I don’t see how. It’s not as if India’s degraded environment had no parent till this judgment came along. The Uttarakhand Environment Protection and Pollution Control Board (UEPPCB) is a statutory Organization constituted under the section 4 of Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 to implement environmental laws and rules within the jurisdiction of Uttarakhand. It’s their job to keep the rivers clean. When it comes to encroachment, the Uttarakhand Urban and Country Planning And Development Act, 1973 sends anyone encroaching on public land to jail for a year with a fine of twenty thousand. It also authorizes the authority under the Act to remove the encroachment. To put it quite bluntly, I do not see how making a new bunch of officers responsible for fixing an old problem changes anything of the nature of the problem.

This brings me to the two thoughts I have on this issue. First, I am gravely concerned with issues around materiality. I have argued in the past that Indian courts assume jurisdiction orders of magnitude beyond the powers that were conferred on them when their existence was conceived. Thus I have argued in Invisible Elephant in the Court Room that it is not for courts to expend their energy rendering judgement on the legality of bull taming, anthem standing and santa-banta joke telling. Departments already exist to protect rivers, keep waters clean, prevent encroachments, and so forth. If citizens flout the law and the government watches immobile, laws also exist to move the courts to make governments do their job. These prerogative writs are well known and frequently employed to excellent effect by the courts. In the circumstances, there is little benefit in creating new judicially imagined realities that do nothing to advance the cause of the issue at hand. In India, this above all is true: when we confront a problem, we deny that we are poorly administered. Instead, we pretend the law is inadequate and set out to create another law which inevitably is just as ineffective no matter how effectively it is drafted. We need to recognize that it’s rarely the law: it’s the attitude of its enforcers. If we want to change behaviour, we have to change incentives, not switch enforcers.

My second thought is a national reality we need to confront. We are a nation of grandstanders who engage in endless pulpit oratory and ‘tokenism’. If we want to clean up our country, it doesn’t strike us that organization, process and best practice is quite the way to go. Instead we think the best way to do it is to hand a broom to every celebrity we can find and have them mill about on a pleasant Sunday winter afternoon amidst leering bystanders fighting to get into the TV frame. It’s not entirely different with the courts. Importing Hindutva into what is above all a management challenge of managing municipal and industrial waste is erudite spin unlikely to address the issue. The Pollution Board must by law clean water bodies whether they provide us spiritual sustenance or not. The Ganga is beautiful even if she isn’t a full bodied goddess. Engaging in literary flourishes may excite the press, but it does not do enough to advance the debate or resolve the issue at hand.